Waste and belief

Marc Herbst

23/08/03

Idaho, USA

"Thoughts on nuclear/deep time/ ecology, or the rural/urban What is your previous experience working on the nuclear topic?"

I was a fellow for the Holding What Can't be Held art project sponsored by the Boise Idaho Snake River Alliance, and organized by artist/curator Tim Andraea. The Snake River Alliance is an anti-nuclear watchdog, green energy and water steward for the Snake River which weaves its way through Idaho and Washington. It has been active since the 1970's, when the toxic legacies of the American nuclear program came to the surface through the disaster at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania and the spectacular uncovering of the toxic stew at Rocky Flats in Colorado.

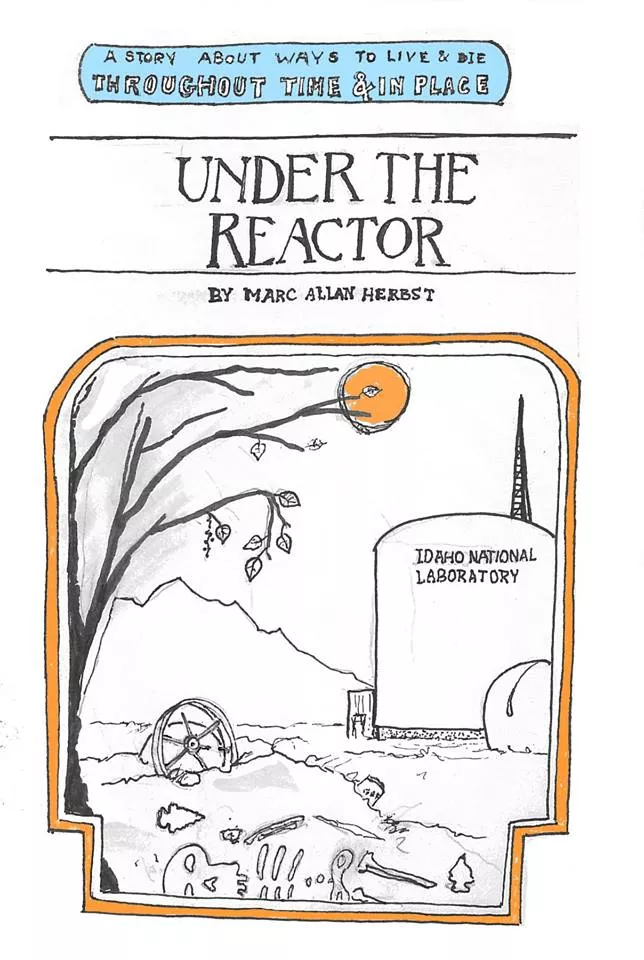

Through persistent activism, the Alliance forced the Idaho National Laboratory (INL) to clean up the pits of nuclear waste that were at risk of leaking into the precious groundwater of the dry intermontain west. They also were able to stop any delivery of nuclear waste to the site.

Tim Andreae, an artist and board member of the Alliance recognized the fragility of social movement that birthed it. He saw their values and commitment to care for our waste and the shared earth. So he began curating the "Holding What Can't be Held" project to keep their mission in public focus. Holding What Can't be Held invites selected international and local artists for a research trip to the INL. The artists are then asked to meditate on questions of nuclear energy and waste for a year. After that year's contemplation, they are invited to contribute to a group exhibition at Ming Gallery in Boise.

The project has been running since 2014.

My contribution to the project focused on three peoples' changing theological understanding around relationship to earth. I focused on the Native American, main-stream Christian, and Mormon peoples who populated the region from Western settlement until today. During the original settlement until today, the region's Nez Pierce, Paiute and Bannock peoples expressed stunning ecological awareness around their connections to the earth.

In the 19th century, Smohalla of the region's Walla Walla tribe said, "My young men shall never work, men who work cannot dream; and wisdom comes to us in dreams. You ask me to plow the ground. Shall I take a knife and tear my mothers breast? Then when I die she will not take me to her bosom to rest. You ask me to dig for stone. Shall I dig under her skin for her bones? Then when I die I cannot enter her body to be born again."

Overall, through the lens of nuclear power and waste, I was taken by how radically different Idaho was 150 years ago-barely colonized- with one band of Nez Pierce still actively resisting colonization, and a local Paiute named Wodziwob having founded the world-renewing Ghost Dance. Wodziwob, influenced by Christianity and perhaps the then communitarian millenarianism of the region's oppressed Mormons, began teaching the Dance to all tribes who would listen. He and others traveled by train to Dance a new world. The US Army's massacre of mostly Lakota Ghost Dancers at Wounded Knee in 1890's is seen by many as the final chapter of the US West's colonizing period. It was right around that time that the region's Mormons went from a more utopian socialist model for organizing to modeling themselves off of mainline Christian individualism. It is in the light of the individual, divorced from community and nature that I experienced the dangers of nuclear power and its wastes at the INL.